-40%

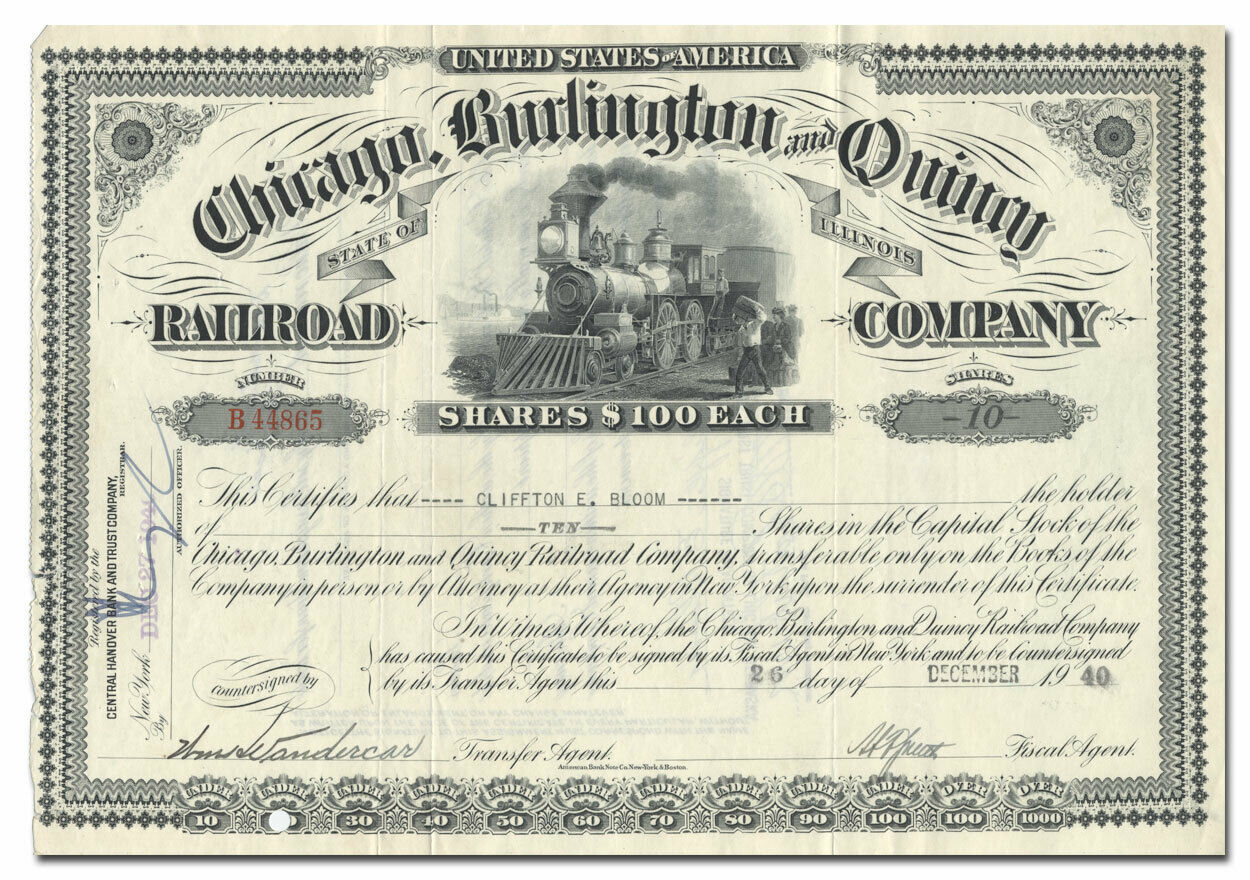

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Company Stock Certificate (1800's)

$ 6.33

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

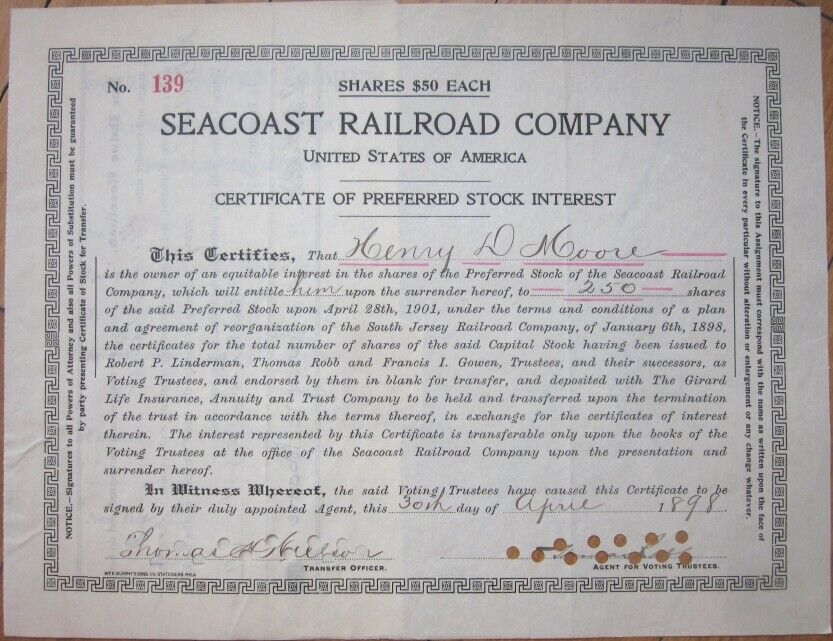

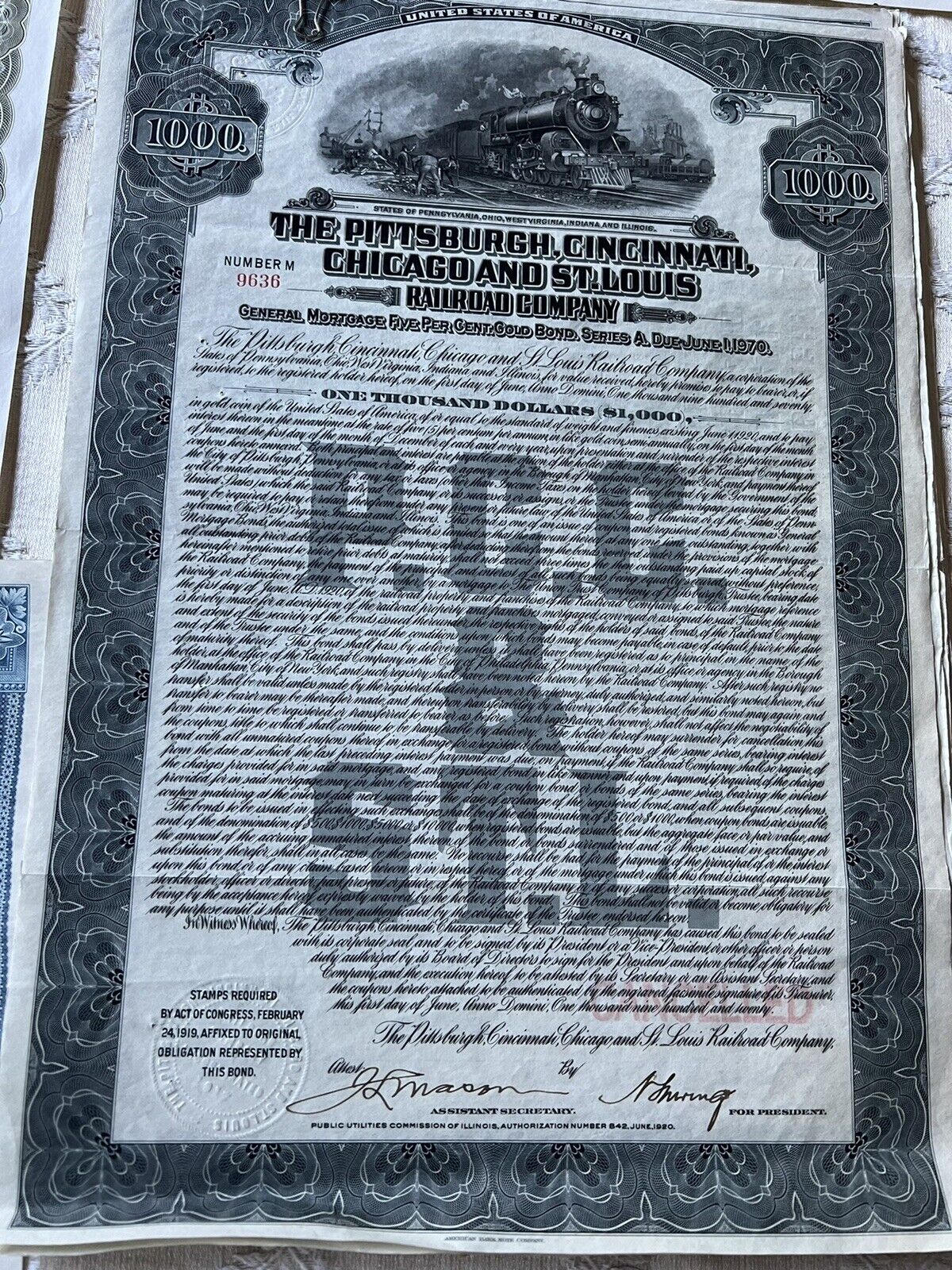

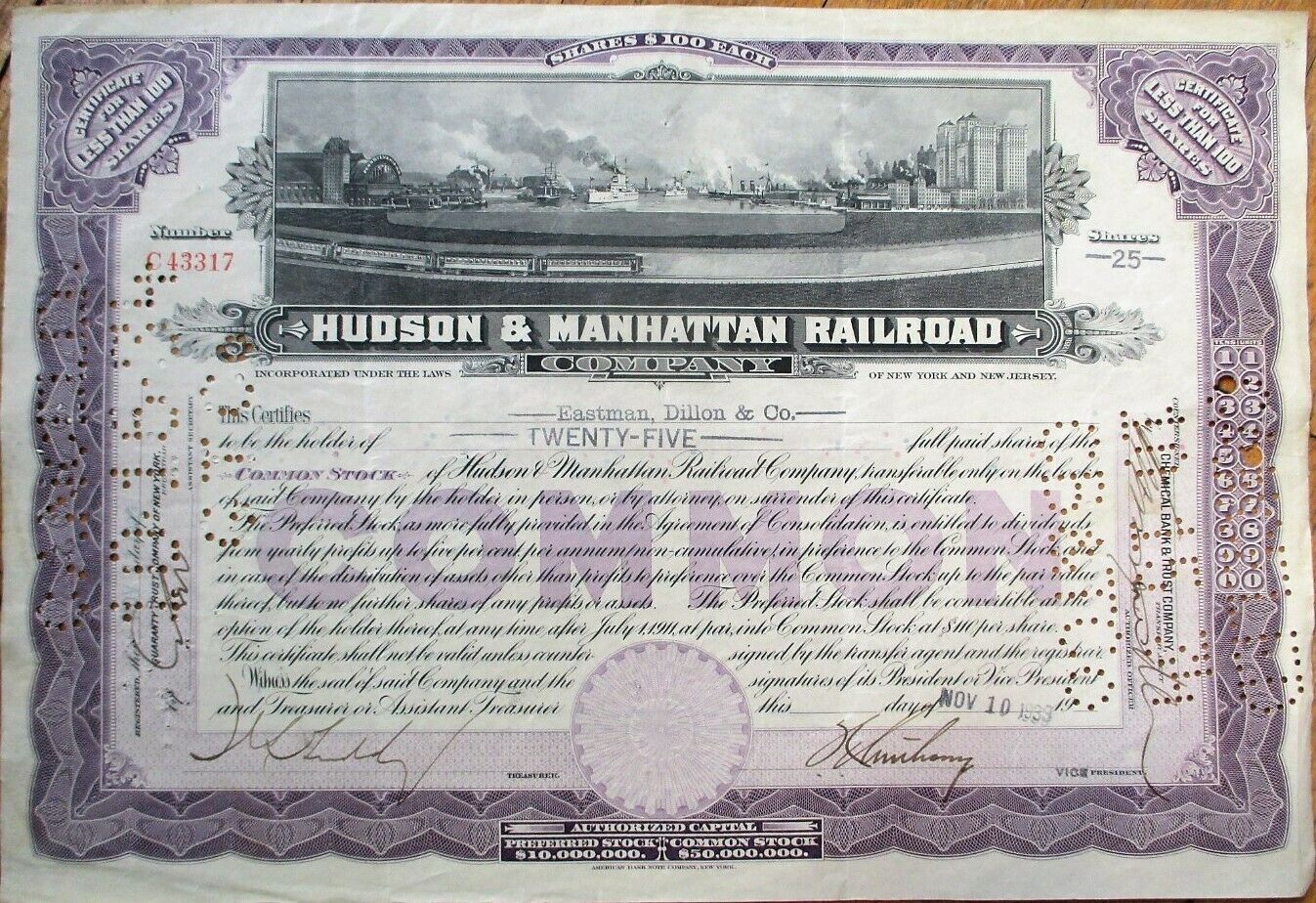

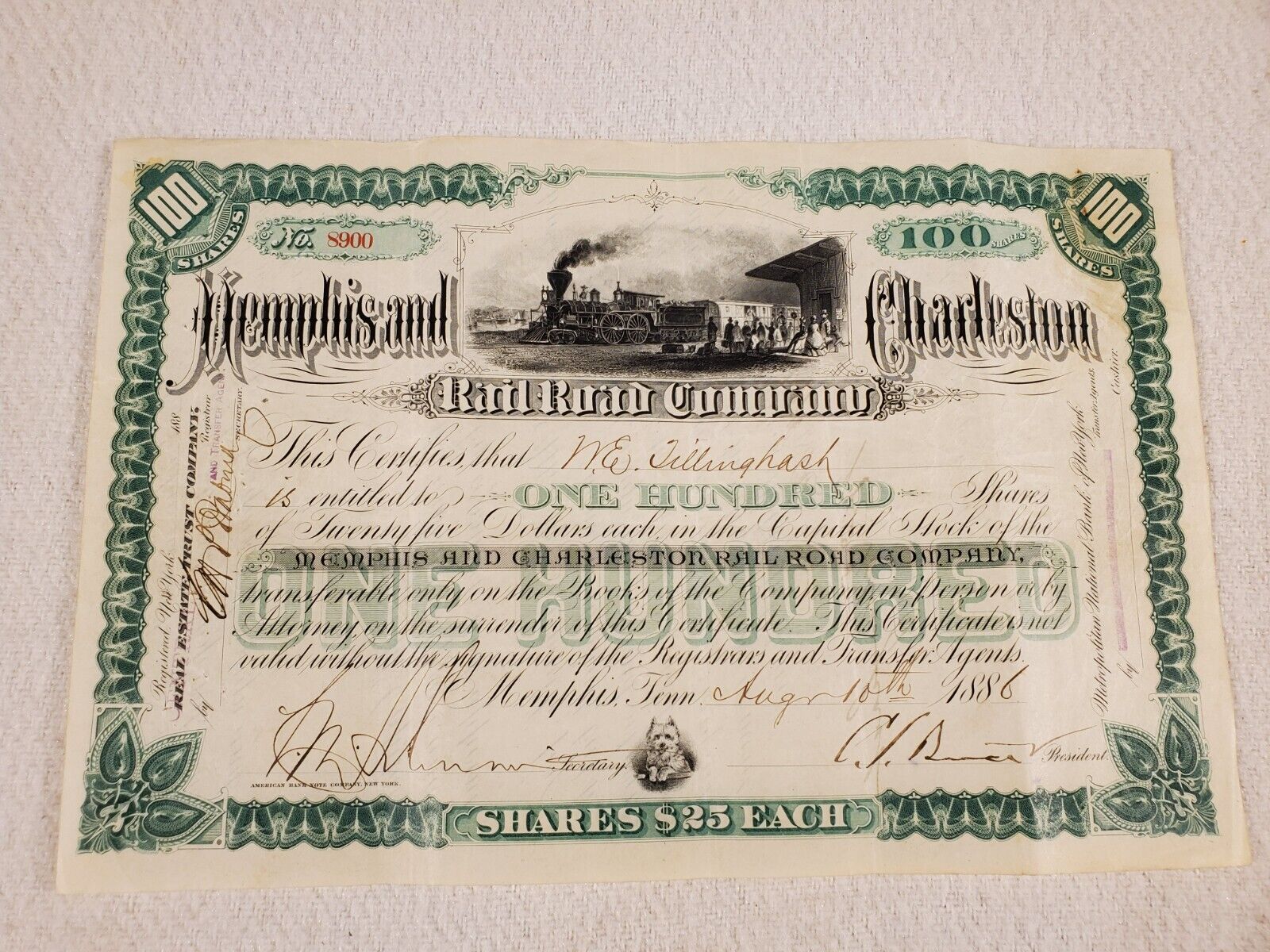

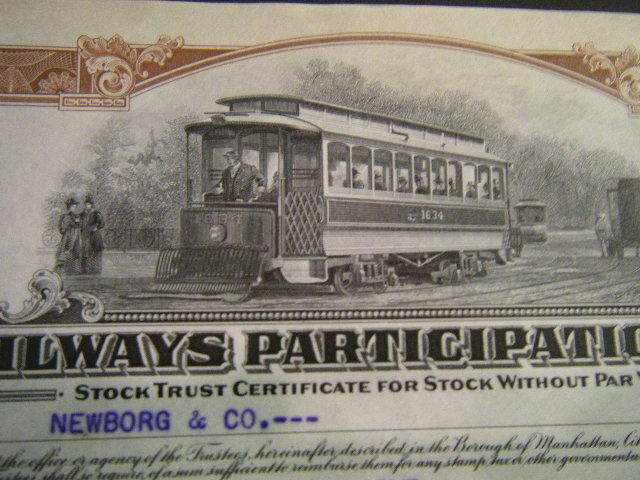

Product DetailsBeautifully engraved antique stock certificate from the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Company dating back to the 1880's. This document was printed by the American Bank Note Company and measures approximately 10 1/2" (w) by 7 1/2" (h).

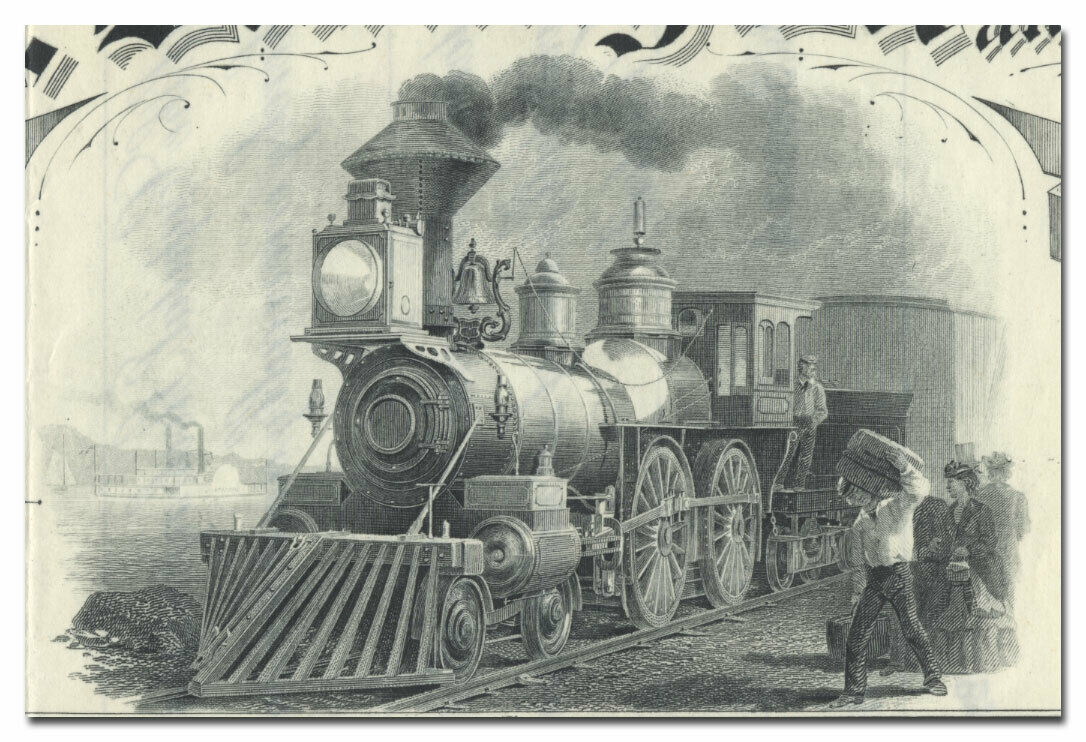

This certificate contains a very detailed vignette of a train passing a group of workers and passengers.

Images

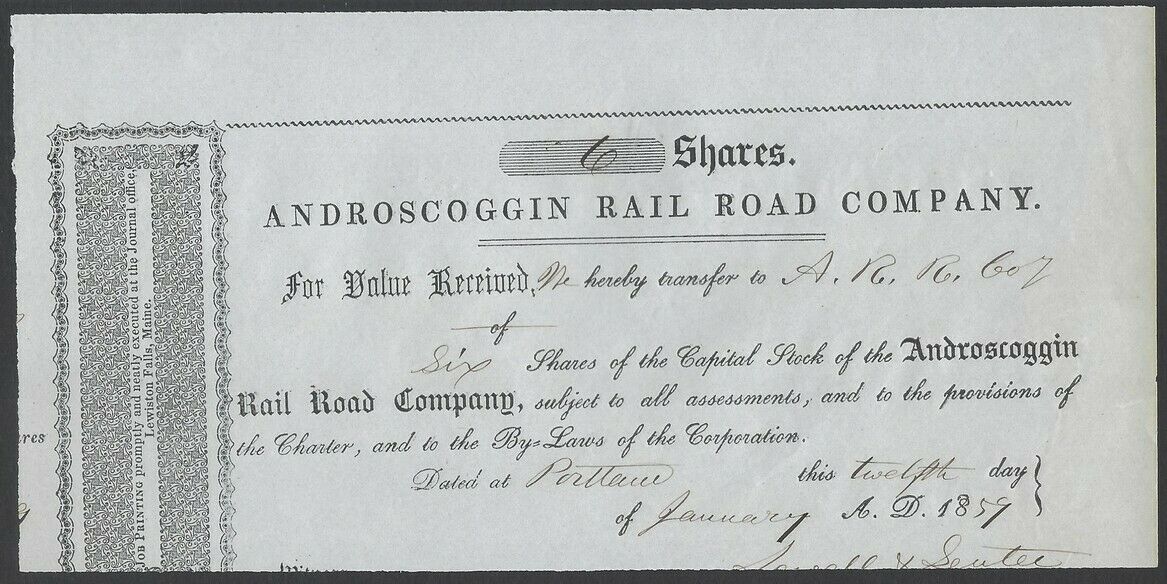

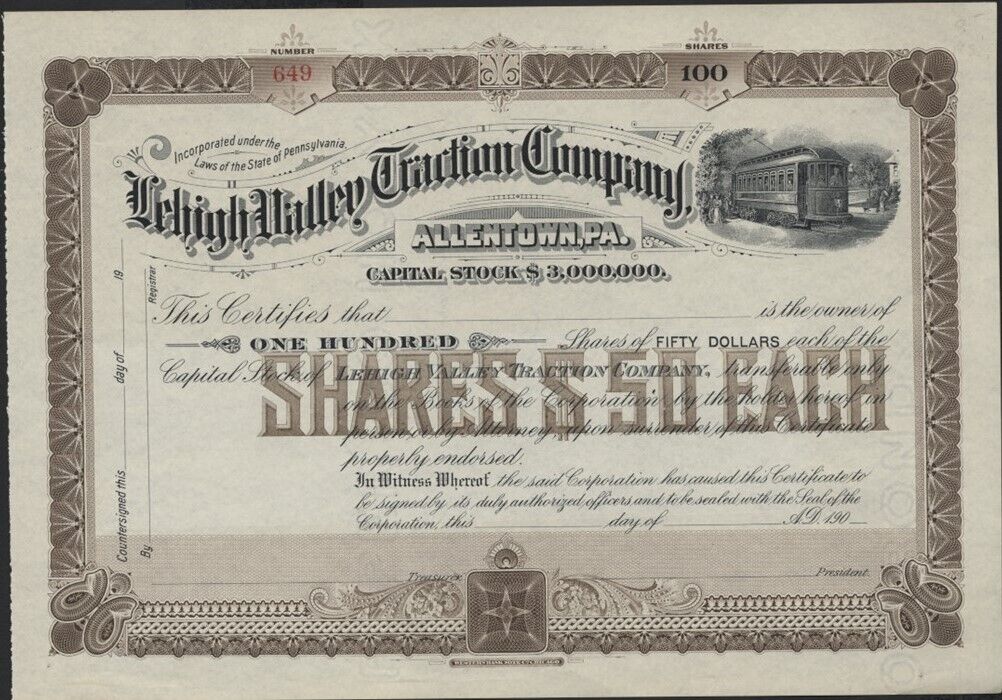

The images presented are representative of the piece(s) you will receive. When representative images are presented for one of our offerings, you will receive a certificate in similar condition as the one pictured; however dating, denomination, certificate number and issuance details may vary.

Please note the brown and black pieces both have accordian cut cancels in the body.

Historical Context

The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad was commonly referred to as the Burlington or as the Q, the railroad served a large area, including extensive trackage in the states of Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Wyoming. Its primary connections included Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, St. Louis, Kansas City and Denver. Because of this extensive tracking in the midwest and mountain states the Q used the slogans "Everywhere West," "Way of the Zephyrs," and "The Way West."

History

The earliest forefather of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, the Aurora Branch Railroad, was chartered by act of the Illinois General Assembly on October 2, 1848. The citizens of Aurora and Batavia, Illinois, did this out of concern for Galena and Chicago Union Railroad bypassing their towns in favor of West Chicago on its route, which, at the time, was the only line running west from Chicago. The Aurora Branch was henceforth built from Aurora, through Batavia, to Turner Junction in what is now West Chicago. Using a leased locomotive and cars, old strap rail, and minimal, if any, grading, the AB eventually began running passenger and freight trains from Aurora to Chicago by running its trains from Aurora to Turner and then using one of the G&CU's two tracks east from there to Chicago. The G&CU required the Aurora Branch to turn over 70 percent of their revenue per ton-mile handled on that railroad; as a result, surveys were ordered to determine the best route for a railroad line to Chicago.

In 1862, the line from Aurora to Chicago, built through the fledgling towns of Naperville, Downers Grove, Hinsdale, Berwyn, and the west side of Chicago, was opened and passenger and freight service began. Regular commuter train service started in 1863 and remains operational to this day, making it the oldest surviving regular passenger service in Chicago. Both the original Chicago line, and to a much lesser extent, the old Aurora Branch right of way, are still in regular use today by the Q's descendant BNSF Railway.

With a steady acquisition of locomotives, cars, equipment, and trackage, the Burlington Route was able to enter the trade markets in 1862. As of that year, that railroad has been the only Class I U.S. railroad to constantly pay dividends and never run into debt or default on a loan.

After extensive trackwork was planned, the Aurora Branch changed its name to the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad and shortly reached its two other namesake cities, Burlington, Iowa and Quincy, Illinois. In 1868 the CB&Q completed bridges over the Mississippi River both at Burlington, Iowa and Quincy, Illinois giving the railroad through connections with the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad (B&MR) in Iowa and the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad (H&StJ) in Missouri. The first Railway Post Office was inaugurated on the H&StJ to sort mail on the trains way across Missouri, passing the mail to the Pony Express upon reaching the Missouri River at St. Joseph, Missouri. The B&MR continued building westward into Nebraska as a separate company, the Burlington & Missouri River Rail Road in Nebraska, founded in 1869. During the summer of the following year, it reached Lincoln, the newly designated capital of Nebraska and by 1872 it reached Kearney, Nebraska. That same year the B&MR across Iowa was absorbed by the CB&Q. By the time the Missouri River bridge at Plattsmouth, Nebraska was completed the B&MR in Nebraska was well on its way to the Mile High city of Denver, Colorado. That same year, the Nebraska B&MR was purchased by the CB&Q which completed the line to Denver by 1882, the first direct rail line from Chicago to Denver.

Burlington's rapid expansion after the Civil War was based upon sound financial management, dominated by John Murray Forbes of Boston and assisted by Charles Elliott Perkins. Perkins was a powerful administrator who eventually forged a system out of previously loosely-held affiliates, virtually tripling Burlington's size during his presidency from 1881 to 1901.

Ultimately, Perkins' believed the Burlington must be included into a powerful transcontinental system. Though the Burlington reached as far west as Denver, Colorado and Billings, Montana, it had failed to reach the Pacific Coast during the cheaper building years of the latter part of the 19th century. Though approached by E.H. Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad, Perkins' felt the Burlington was a more natural fit with James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway. With its river line to the Twin Cities, the Burlington formed a natural connection between Hill's home town (and headquarters) of St. Paul, Minnesota, and the all-important American railroad hub of Chicago. Moreover, Hill was willing to meet Perkins' 0-a-share asking price for the Burlington's stock. By the turn of the century, Hill's Great Northern, in conjunction with the Northern Pacific Railway, held nearly 100 percent of the Burlington's stock.

In 1901 a rebuffed Harriman tried to gain an indirect influence over the Burlington by launching a stock raid on the Northern Pacific. Though Hill managed to fend off this attack on his nascent system, it led to the creation of the Northern Securities Company, and later, the U.S. Supreme Court's Northern Securities Decision.

With the First World War having the same effect on the Burlington as on all other railroads, the Burlington Route had an increasingly heavy amount of equipment flooding the yards. With the advent of the Great Depression, the CB&Q held a good portion of this for scrap. Despite the decrease of passengers, it was during this time that the Q introduced the famed Zephyrs.

As early as 1897, the Q had been interested in alternatives to steam power, namely, internal-combustion engines. The Aurora Shops had built a clumsy and totally unreliable three-horsepower distillate motor in that year, but it was hugely impractical (requiring a massive 6,000-pound flywheel) and had issues with overheating (even with the best metals of the day, its cylinder heads and liners would warp and melt in a matter of minutes) and was therefore impractical. Diesel engines of that era were obese, stationary monsters best suited for low-speed, continuous operation. None of that would do in a railroad locomotive; however, there was no diesel engine suitable for that purpose then.

Always innovating, the Q both purchased "doodlebug" gas-electric combine cars from Electro-Motive Corporation and built their own, sending them out to do the jobs of a steam locomotive and a single car. With good success in that field, and after having purchased and tried a pair of General Electric steeple-cab switchers powered by distillate engines, Q president Ralph Budd requested of the Winton Engine Company a light, powerful diesel engine that could stand the rigors of continuous, unattended daily service. The experiences of developing these engines can be summed up shortly by General Motors Research vice-president Charles Kettering: "I do not recall any trouble with the dip stick." Ralph Budd, accused of gambling on diesel power, chirped that "I knew that the GM people were going to see the program through to the very end. Actually, I wasn't taking a gamble at all." The manifestation of this gamble was the eight-cylinder Winton 8-201A diesel, a creature no larger than a small Dumpster, that powered the Burlington Zephyr on its record run and opened the door for developing the long line of diesel engines that has powered Electro-Motive locomotives for the past seventy years.

After the Second World War, the CB&Q was inundated by the overworked steam locomotives existent in a fleet that was already beginning to dieselize. Having expanded its dieselization program rapidly, steam power was slowly put out to pasture, and on September 28, 1959, the last steam-powered commuter train from Chicago rolled to a stop in Downers Grove, marking the end of the steam era on the CB&Q.

As the financial situation of American railroading continued to decline, the Burlington merged with the Great Northern Railway, Northern Pacific and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle railroads to form the Burlington Northern Railroad, a merger once dreamed of by Great Northern founder James J. Hill.

The Burlington Zephyrs

The railroad operated a number of streamlined passenger trains known as the Zephyrs which were the most famous and largest fleet of streamliners in the United States. The "Burlington Zephyr," America's first diesel-electric powered streamlined passenger train, made its famous "Dawn-to-Dusk" run from Denver, Colorado to Chicago, Illinois on May 26, 1934. On November 11, 1934 the train was put into regularly scheduled service between Lincoln, Nebraska and Kansas City, Missouri. Although the distinctive, articulated stainless steel trainsets were well known, and the railroad adopted the "Way of the Zephyrs" slogan, they did not attract passengers back to the rails en masse, and the last one was retired from revenue service with the advent of Amtrak.

The Zephyr service included:

Pioneer Zephyr (Lincoln–Omaha–Kansas City)

Twin Cities Zephyr (Chicago–Minneapolis-St. Paul)

Mark Twain Zephyr (St. Louis–Burlington)

Denver Zephyr (Chicago–Denver)

Nebraska Zephyr (Chicago–Lincoln)

Sam Houston Zephyr (Houston–Dallas-Ft. Worth)

Ozark State Zephyr (Kansas City–St. Louis)

General Pershing Zephyr (Kansas City–St. Louis)

Silver Streak Zephyr (Kansas City–Omaha–Lincoln)

Ak-Sar-Ben Zephyr (Kansas City–Omaha–Lincoln)

Zephyr-Rocket (St. Louis–Minneapolis-St. Paul)

Texas Zephyr (Denver–Dallas-Ft. Worth)

American Royal Zephyr (Chicago–Kansas City)

Kansas City Zephyr (Chicago–Kansas City)

California Zephyr (Chicago–Oakland)

The California Zephyr is still operated daily today by Amtrak as trains 5 (westbound) and 6 (eastbound). Another train, the Illinois Zephyr, is a modern descendant of the Kansas City Zephyr and American Royal Zephyr service.

Innovations

The Burlington was a leader in implementing technological innovation; among its firsts were use of the printing telegraph, train radio communications, streamlined passenger diesel power and vista-dome coaches. In 1927, the Burlington was one of the first to utilize Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) and by the end of 1957 had equipped 1,500 miles of its right-of-way for this advanced type of signaling. The Q had one of the first hump classification yards at its Western Avenue Yard in Chicago, allowing an operator in a tower to line switches remotely and making around-the-clock classification a fact. Today, as BNSF, they are still a leader in innovation, by adopting the new "AC Traction Control" in new diesel locomotives.